ST MARY AND ST BOTOLPH. A monastery was founded here c.670. It was destroyed in the Danish raid of 870 and re-founded in 972 for Benedictine monks. After the Conquest Abbot Guenther rebuilt the church. He must have begun immediately after he had been elected in 1085; for in 1089 the monks could move in. By 1098 the chancel and crossing tower were ready. The church was completed in 1108, though consecrated only in 1128. All that remains of it is part of the nave, shorn of its aisles and of its E end. The total original length was nearly 300 ft. However, the crossing, with crossing tower, the transepts and chancel, and practically all the monastic buildings have disappeared. The present E end is by Blore, in the Norman style, 1840-1. The original fragment, inadequate as it may be, is yet very impressive, owing chiefly to its tall W front. This is a composite structure to which the C12, the C15, and the C17 have contributed. Norman are the angle turrets, starting as broad buttresses and continued octagonal. They end in Perp battlements. These buttresses originally separated the W end of the nave from that of the aisles. Their stepped plan makes it probable that the Norman W front of Thorney had three giant niches on the pattern of C11 Lincoln. Perp W window partly blocked; probably Perp the doorway. In 1638 the ruined church was restored as the parish church of Thorney. It was then that, to the l. and r. of the doorway, blank arcades were carved with ogee heads and a frieze above decorated with heads like fleurons. All this is in a typical imitation-Perp of which a contemporary example is e.g. Peterhouse Chapel at Cambridge. The Perp W window may belong to the same date. Along the N and S sides the design of the Norman arcades can be studied, as the arcade openings were blocked in 1638, when the aisles were pulled down. One bay of the Norman clerestory also survives, a plain arched window (blocked) on the S side, but decorated by billet friezes on the N. The interior elevation is quite evident when one enters the church. The arcades are designed with alternating supports, but the principal motif, the shaft rising without interruption from floor to ceiling, is the same everywhere. The design towards the arch openings, however, differs between segments of fat circular projection and three stepped shafts - just as at Ely. The arches are single-stepped, but the capitals are scalloped. The gallery openings are not subdivided (cf. e.g. Colchester St Botolph). They are now filled with C15 tracery, perhaps from the former clerestory. The piers have two shafts towards the openings, and the arches two roll mouldings. The capitals are mostly of the primitive volute type, but others are also scalloped. - STAINED GLASS. German or Swiss panels in the nave E windows. - The E window is a copy from Canterbury. - PLATE. Cup and Paten of 1709; Almsdish of 1750.

THORNEY. Thorney’s natural beauty is all the more enhanced because of its place in the plain fenlands. Its lanes are perfect bowers of greenery, gabled houses are everywhere, and there is a fine green space by the church in which the village is passing rich, both for itself and for its story. For this is holy ground, and this island in the fens, once an oasis in a wilderness of marshes, is a witness of the thousand year struggle of Englishmen for their altars and their homes.

Grand as it is today in its simplicity and strength, the Abbey Church has come through much change of fortune to be but a fragment of its old self which was five times as big when the Normans left it, and it is the only part extant of the monastery founded here for anchorites in 662, though traces of foundations of the monastic buildings have been found. Its story begins when Wulpher, King of the Mercians, went to Peterborough in 662 for the consecration of the minster. Saxulph, the Abbot, told him that some of his monks wished to live the hermit’s life, and the king granted them permission to retire to dreary Thorney Island in the marshes. There they dwelt in huts and built themselves a chapel, and though little is known of them their names are not wholly forgotten. Tancred, Tortred, and their sister Tona were for ever remembered for their renunciation, and sleep as canonised saints somewhere beneath the stones of the once great Abbey Church.

Other saints found the same sanctuary, but not all can be said to have rested in peace, for the Danes swept down on the monastery, burning and pillaging, and the monks took refuge in the woods. In 972 it was refounded by Ethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and King Edgar endowed it. A hundred years later the monastery suffered at the hands of its friends, for when Hereward the Wake made his stand against the Conqueror Thorney Island was one of his fastnesses, and suffered in the attack.

Then, in the last years of the Conqueror’s reign, a change took place in its fortunes. Thorney was born again. The old Saxon church was taken down and a new great one raised in its stead, and with its new foundation there was born a new vigour in well-doing. William of Malmesbury paid a tribute not merely to the piety of the monks, but to their courage and industry in coping with the fenland. A very paradise bearing trees, he called it, extolling the vines and apples of this wonderful solitary place for monks of quiet life. The abbey buildings were enlarged from time to time, and a chapter house was built early in the 14th century where the vicarage is now, and the abbey gateway was renowned in the same century for being “one of the hundred celebrated places in England.” The place grew in fame, and its mitred abbot sat in the House of Lords till the Dissolution, when the monks were driven away, the lead of the roofs was stripped and melted down in fires fed perhaps by the woodwork of the Abbey Church, and of its stones 140 tons were taken for building the new chapel of Corpus Christi College. The fruitful fields went back to marshland and desolation.

Nearly a century passed, and there was another turn of fortune’s wheel. It began with the great adventure, led by the Earl of Bedford, of draining the fens, and one of the chapters in that story included the restoration of the remains of the Abbey Church in 1638. Inigo Jones is said to have been the architect.

Gone are the six aisles, the central tower, and the spires which crowned the western towers of the Norman church, which was nearly 300 feet long, but it stands majestic in the shape of a T formed by the old nave with its splendid west front, and transepts added at its eastern end last century. The Norman masonry gleams light and lovely in contrast with the 19th century’s rust-coloured stone. The five great bays of the Norman arcades now in the side walls are magnificent, some of the round arches on clustered pillars. Under the arches, and in the Norman triforium above them, the later windows are set. The imposing west front is mainly Norman, though later turrets crown the two Norman towers which flank it, and are now 83 feet high. A smaller window lights the west wall, set in an earlier arch which rises to a fine gallery of nine saints in niches, who are thought to have either lived at Thorney or to have been buried here. The third in the row, from the right, is Tatwin, a hermit here who took St Guthlac in a boat to Croyland when he was finding a site for his hermitage.

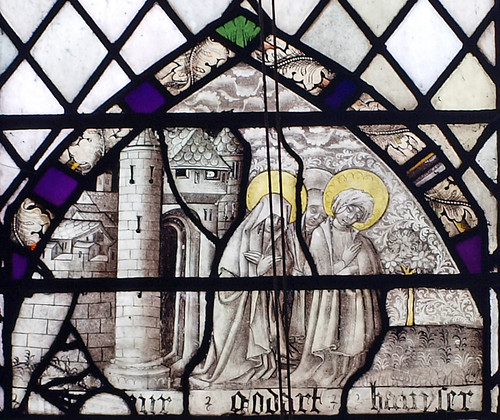

The east window is a great lancet without tracery, about a century old and striking with a rich mosaic of roundels in purple tones glinting with gold and greens, representing the miracles of Thomas Becket. It is a copy of a window in Canterbury Cathedral. Other windows have old shields of the Duke of Bedford, John of Gaunt, and Henry the Eighth and Catherine of Aragon, and lovely Flemish panels with scenes of Bible story, among them a fine Pieta, the Upper Room at Emmaus, and Christ receiving the saved from a tomb, with a demon trapped under His feet and another demon fleeing.

A tablet on the wall gives us another strange chapter of Thorney’s story. It is a French inscription to Ezekiel Danois of Compiégne in France, the first minister of the Huguenot colony which fled to England to escape persecution and settled here. He was a worthy successor to Thorney’s saints, and we read that “in unwearied zeal, learning, and strictness of life, he was second to none; a great treasure of literature was here hidden from the world, known to God and himself, few besides.” Twenty-one of his 54 years of service were spent at Thorney Abbey, and he was buried here in 1674. It is one of the strangest episodes in Thorney’s history that Huguenot pastors continued to minister here till 1715.

Grand as it is today in its simplicity and strength, the Abbey Church has come through much change of fortune to be but a fragment of its old self which was five times as big when the Normans left it, and it is the only part extant of the monastery founded here for anchorites in 662, though traces of foundations of the monastic buildings have been found. Its story begins when Wulpher, King of the Mercians, went to Peterborough in 662 for the consecration of the minster. Saxulph, the Abbot, told him that some of his monks wished to live the hermit’s life, and the king granted them permission to retire to dreary Thorney Island in the marshes. There they dwelt in huts and built themselves a chapel, and though little is known of them their names are not wholly forgotten. Tancred, Tortred, and their sister Tona were for ever remembered for their renunciation, and sleep as canonised saints somewhere beneath the stones of the once great Abbey Church.

Other saints found the same sanctuary, but not all can be said to have rested in peace, for the Danes swept down on the monastery, burning and pillaging, and the monks took refuge in the woods. In 972 it was refounded by Ethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and King Edgar endowed it. A hundred years later the monastery suffered at the hands of its friends, for when Hereward the Wake made his stand against the Conqueror Thorney Island was one of his fastnesses, and suffered in the attack.

Then, in the last years of the Conqueror’s reign, a change took place in its fortunes. Thorney was born again. The old Saxon church was taken down and a new great one raised in its stead, and with its new foundation there was born a new vigour in well-doing. William of Malmesbury paid a tribute not merely to the piety of the monks, but to their courage and industry in coping with the fenland. A very paradise bearing trees, he called it, extolling the vines and apples of this wonderful solitary place for monks of quiet life. The abbey buildings were enlarged from time to time, and a chapter house was built early in the 14th century where the vicarage is now, and the abbey gateway was renowned in the same century for being “one of the hundred celebrated places in England.” The place grew in fame, and its mitred abbot sat in the House of Lords till the Dissolution, when the monks were driven away, the lead of the roofs was stripped and melted down in fires fed perhaps by the woodwork of the Abbey Church, and of its stones 140 tons were taken for building the new chapel of Corpus Christi College. The fruitful fields went back to marshland and desolation.

Nearly a century passed, and there was another turn of fortune’s wheel. It began with the great adventure, led by the Earl of Bedford, of draining the fens, and one of the chapters in that story included the restoration of the remains of the Abbey Church in 1638. Inigo Jones is said to have been the architect.

Gone are the six aisles, the central tower, and the spires which crowned the western towers of the Norman church, which was nearly 300 feet long, but it stands majestic in the shape of a T formed by the old nave with its splendid west front, and transepts added at its eastern end last century. The Norman masonry gleams light and lovely in contrast with the 19th century’s rust-coloured stone. The five great bays of the Norman arcades now in the side walls are magnificent, some of the round arches on clustered pillars. Under the arches, and in the Norman triforium above them, the later windows are set. The imposing west front is mainly Norman, though later turrets crown the two Norman towers which flank it, and are now 83 feet high. A smaller window lights the west wall, set in an earlier arch which rises to a fine gallery of nine saints in niches, who are thought to have either lived at Thorney or to have been buried here. The third in the row, from the right, is Tatwin, a hermit here who took St Guthlac in a boat to Croyland when he was finding a site for his hermitage.

The east window is a great lancet without tracery, about a century old and striking with a rich mosaic of roundels in purple tones glinting with gold and greens, representing the miracles of Thomas Becket. It is a copy of a window in Canterbury Cathedral. Other windows have old shields of the Duke of Bedford, John of Gaunt, and Henry the Eighth and Catherine of Aragon, and lovely Flemish panels with scenes of Bible story, among them a fine Pieta, the Upper Room at Emmaus, and Christ receiving the saved from a tomb, with a demon trapped under His feet and another demon fleeing.

A tablet on the wall gives us another strange chapter of Thorney’s story. It is a French inscription to Ezekiel Danois of Compiégne in France, the first minister of the Huguenot colony which fled to England to escape persecution and settled here. He was a worthy successor to Thorney’s saints, and we read that “in unwearied zeal, learning, and strictness of life, he was second to none; a great treasure of literature was here hidden from the world, known to God and himself, few besides.” Twenty-one of his 54 years of service were spent at Thorney Abbey, and he was buried here in 1674. It is one of the strangest episodes in Thorney’s history that Huguenot pastors continued to minister here till 1715.

No comments:

Post a Comment